Orson Welles reads Kafka.

"Every man strives to attain the law."

Monday, March 31, 2014

Saturday, March 29, 2014

Unnaturally extreme social needs

"It's not that I'm not social. I'm social enough. But the tools you guys create actually manufacture unnaturally extreme social needs. No one needs the level of contact you're purveying. It improves nothing. It's not nourishing. It's like snack food. You know how they engineer this food? They scientifically determine precisely how much salt and fat they need to include to keep you eating. You're not hungry, you don't need the food, it does nothing for you, but you keep eating these emptying calories. This is what you're pushing. Same thing. Endless empty calories, but the digital-social equivalent. And you calibrate it so it's equally addictive."— from The Circle, by Dave Eggers.

Yes! That's the world exactly.

(As the novel progresses, there's a creeping sense of unease. Clearly something bad is going to happen to sweet Mae, new employee of the Circle, modelled after real-life Google.)

My reading is enhanced this week by watching Google and the World Brain, in which Kevin Kelly relates how Larry Page said, "It's not to make a search engine, it's to make an AI."

Also, "Google's Earth" by William Gibson: "We are its unpaid content-providers [...]. Google is made of us."

Labels:

Dave Eggers,

William Gibson

Friday, March 28, 2014

Everyone always mistakes everyone for someone else

The Letter Killers Club, by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, is a strange little excuse for a novel.

I want to love it, but I don't quite. For such a short novel, it took an amazingly long time to read. It's full of interesting ideas that aren't completely developed, aren't resolved, don't completely gel. The novel is a fantastic cerebral exercise, but it leaves me cold.

The club is a secret society of men known only by nonsense syllables. They are "conceivers" — in the interest of purity, nothing is committed to paper. They meet weekly and tell stories that span genres, subjects, and formats.

But it's the framing story that captivates me — who are these men, why do they meet, what is so subversive in it, why must it be so secret? where is the political element? for it feels like there must be one.

Here are some of the themes strewn across these pages.

See also

The Millions: Storytelling is a Deadly Business: Krzhizhanovsky's The Letter Killers Club

The Rumpus: Against an Ethical Machine

I want to love it, but I don't quite. For such a short novel, it took an amazingly long time to read. It's full of interesting ideas that aren't completely developed, aren't resolved, don't completely gel. The novel is a fantastic cerebral exercise, but it leaves me cold.

A conception without a line of text, I argued, is like a needle without thread: it pricks, but does not sew.That's how I feel about this book.

The club is a secret society of men known only by nonsense syllables. They are "conceivers" — in the interest of purity, nothing is committed to paper. They meet weekly and tell stories that span genres, subjects, and formats.

But it's the framing story that captivates me — who are these men, why do they meet, what is so subversive in it, why must it be so secret? where is the political element? for it feels like there must be one.

Here are some of the themes strewn across these pages.

I walked quickly — from crossroad to crossroad — trying to untangle my feelings. The evening seemed like a black wedge driven into my life. I had to unwedge it. But how?

**********

I think this is all fairly simple: every three-dimensional being doubles himself twice — reflecting himself outwardly and inwardly. Both reflections are untrue: the cold, flat likeness returned by the looking glass is untrue because it is less than three-dimensional; the face's other reflection, cast inward, flowing along nerves to the brain and composed of a complex set of sensations, is also untrue because it is more than three-dimensional.

**********

And if the hectic youth who mistook our passer for someone else — racing up, then away — had been able to see through eyes to what is behind them, he would have understood once and for all: everyone always mistakes everyone for someone else.

**********

The fewer the managers, the greater the manageability.

**********

[...] you enter facts from the outside, not the inside, you're worse than your bacteria: they eat the facts, you eat the facts' meanings.

**********

Plotlines throw out disputes the way a plant throws out spores: into space, where they germinate.

See also

The Millions: Storytelling is a Deadly Business: Krzhizhanovsky's The Letter Killers Club

The Rumpus: Against an Ethical Machine

Labels:

NYRB,

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

Inspiration is for amateurs

Last week I went to see Man Booker International Prize-nominated author and creative writing professor Josip Novakovich and two-time Booker Prize-winning author Peter Carey in conversation on stage.

I like Peter Carey, and I'm so relieved that the real-life Peter Carey does not taint my impression of his books, but confirms and enhances my suspicion of the sort of person he is. Wry and unassuming. Observant, clever. Genuine.

On the other hand, I've never read Josip Novakovich. Being a "local" boy (he's called Montreal home for some time), he has flirted with one of my friends. He completely won me over; a little obsessed with death, but in a good way, smart and funny.

The audio file linked to here is a little over an hour, but well worth it. The conversation is moderated; they cover topics including the writing process, inspiration, motivation, editors, how you view "home" when you no longer live there, outsiderness.

Highlights

Josip described in great detail a story he's working on, about a dying man who plans in great detail his own death, funeral, etc. but he — Josip — played it down as something he hasn't fully worked out yet. And Peter cried out, why bother? he's already plotted it out to the point that he — Peter — would lose interest with the project. (Peter himself may plot the skeleton of a journey, but the writing remains a journey of discovery.) And all of this has seeped heavily into my current reading (Krzhizhanovsky's Letter Killers Club) and studying (a MOOC on cognitive poetics) and stained it beyond repair.

Novakovich also said the best advice he ever received from an editor was to cut the first nine pages (and bear in mind that he writes short stories). As an editor, I love hearing anecdotes like this, about finding the real story in a glut of words, finding where the story really starts.

The big takeaway for me was in the discussion of "inspiration is for amateurs," driving home the point that writing is not a romantic notion; it's something they work hard at.

Learn more about the Thinking Out Loud conversation series on the creative process, sponsored by Concordia University and The Globe and Mail.

Peter Carey's latest novel, Amnesia, about a hacker, is due out in November. Why, yes, I do have a birthday around then.

I like Peter Carey, and I'm so relieved that the real-life Peter Carey does not taint my impression of his books, but confirms and enhances my suspicion of the sort of person he is. Wry and unassuming. Observant, clever. Genuine.

On the other hand, I've never read Josip Novakovich. Being a "local" boy (he's called Montreal home for some time), he has flirted with one of my friends. He completely won me over; a little obsessed with death, but in a good way, smart and funny.

The audio file linked to here is a little over an hour, but well worth it. The conversation is moderated; they cover topics including the writing process, inspiration, motivation, editors, how you view "home" when you no longer live there, outsiderness.

Highlights

Josip described in great detail a story he's working on, about a dying man who plans in great detail his own death, funeral, etc. but he — Josip — played it down as something he hasn't fully worked out yet. And Peter cried out, why bother? he's already plotted it out to the point that he — Peter — would lose interest with the project. (Peter himself may plot the skeleton of a journey, but the writing remains a journey of discovery.) And all of this has seeped heavily into my current reading (Krzhizhanovsky's Letter Killers Club) and studying (a MOOC on cognitive poetics) and stained it beyond repair.

Novakovich also said the best advice he ever received from an editor was to cut the first nine pages (and bear in mind that he writes short stories). As an editor, I love hearing anecdotes like this, about finding the real story in a glut of words, finding where the story really starts.

The big takeaway for me was in the discussion of "inspiration is for amateurs," driving home the point that writing is not a romantic notion; it's something they work hard at.

Learn more about the Thinking Out Loud conversation series on the creative process, sponsored by Concordia University and The Globe and Mail.

Peter Carey's latest novel, Amnesia, about a hacker, is due out in November. Why, yes, I do have a birthday around then.

Labels:

Josip Novakovich,

Montreal,

Peter Carey,

writing

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

No one should end his learning while he lives

We are living in 1937 and our universities, I suggest, are not half-way out of the fifteenth century. We have made hardly any changes in our conception of university organisation, education, graduation, for a century — for several centuries. The three- or four-years' course of lectures, the bachelor who knows some, the master who knows most, the doctor who knows all, are ideas that have come down unimpaired from the Middle Ages. Nowadays no one should end his learning while he lives and these university degrees are preposterous. It is true that we have multiplied universities greatly in the past hundred years, but we seem to have multiplied them altogether too much upon the old pattern. A new battleship, a new aeroplane, a new radio receiver is always an improvement upon its predecessor. But a new university is just another imitation of all the old universities that have ever been. Educationally we are still for all practical purposes in the coach and horse and galley stage.— from World Brain, by H.G. Wells.

In this collection of essays, Wells envisions a massive, digitized, permanent World Encyclopedia, accessible to everyone. In 2004, Google announced that it had the same idea. Sort of.

Google and the World Brain is being screened tonight in Montreal.

I'm not able to attend, so I poked around a little and it turns out the film is readily available for viewing online. (But don't tell anyone. Pretty sure it's an infringement of copyright.)

Labels:

education,

H.G. Wells,

movie

Thursday, March 20, 2014

Lettered excesses must be destroyed

"You know, Goethe once described Shakespeare (to Eckermann) as a wildly overgrown tree that — for two hundred years straight — had stifled the growth of all English literature; thirty years later, Börne called Goethe: 'A monstrous cancer spreading through the body of German literature.' Both men were right: if our letterizations stifle one another, if writers prevent each other from writing, they don't allow readers even to form an idea. The reader hasn't the chance to have ideas, the right to them has been usurped by word professionals who are stronger and more experienced in this matter: libraries have crushed the reader's imagination, the professional writings of a small coterie of scribblers have crammed shelves and heads to bursting. Lettered excesses must be destroyed: on shelves and in heads. One must clear at least a little space of other people's conceptions to make room for one's own: everyone has the right to conception — both the professional and the dilettante."— from The Letter Killers Club, by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky.

The Argo Bookshop book club meets March 27 to discuss this book over drinks.

Labels:

bookshop,

Montreal,

NYRB,

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky

Monday, March 17, 2014

Three novels about art, plus

I love art. As the saying goes, I don't know much about art, but I know what I like. Often I feel that I don't have the vocabulary to talk about art. But some writers do.

While nonfiction texts about art might teach me something about technique, form, history, context, I think fiction excels at teaching me to respond to and feel something about art.

Here are three novels that have dealt with art, artists, the art world superbly. (And it's telling that Iwas unable have yet to get around to review a couple of them.)

Art as business

An Object of Beauty, by Steve Martin.

The story follows young and ambitious Lacey Yeager as she climbs through the New York art world, starting in the bins at Sotheby's and finally owning her own gallery. This world is full of art history majors, and generally not people who actually make art.

It doesn't entirely succeed as a novel — I never cared what happened to Lacey. But it's a fascinating glimpse of a world few are wealthy, privileged, or determined enough to see. Steve Martin is a collector of fine art, and this novel is not about art so much as its value, whether to an individual or according to the market.

Note, also, that gorgeous artwork is reproduced within.

Art as an intensely personal expression

The Woman Upstairs, by Claire Messud.

There's a lot of hate in this novel's narrator. Nora, gradeschool art teacher, rediscovers her artistic drive when she befriends the immigrant family of a new student, in particular his mother, an artist looking to share a studio.

Messud explores Nora's art-making and its concept, which in turn relies on Nora's interpretation of the art and biographies of Emily Dickinson, Alice Neel, and Edie Sedgwick.

It's said of Edie Sedgwick, but it may as well be about Nora, perhaps Messud herself:

Hate it for yourself.

Art for art's sake

What I Loved, by Siri Hustvedt.

I loved this novel. It brought me to tears, wonder, astonishment, despair. It's one of the finest novels I've read, ever.

Written from the point of view of an art historian with some artists as characters, it describes the (near?) contemporary art scene and facets like installation art such that I almost think I understand them.

In equal parts family saga, thriller, meditation, I'd say its primarily about love and loss. But its imbued with art, peopled with artists, who do art, who live and breathe art. It makes not just the characters' artistic visions come alive, but the very idea that there exists such a thing as artistic vision becomes crystal clear, and it makes me wonder how anyone could live without art.

Coincidentally, I finally downloaded some of Hustvedt's back catalogue last week. And I was thrilled to discover that she has another novel freshly released, The Blazing World, about a woman painter negotiating New York's art establishment.

Plus

Mark Rothko on the Transcendent Power of Art and How (Not) To Experience His Paintings

While nonfiction texts about art might teach me something about technique, form, history, context, I think fiction excels at teaching me to respond to and feel something about art.

Here are three novels that have dealt with art, artists, the art world superbly. (And it's telling that I

Art as business

An Object of Beauty, by Steve Martin.

The story follows young and ambitious Lacey Yeager as she climbs through the New York art world, starting in the bins at Sotheby's and finally owning her own gallery. This world is full of art history majors, and generally not people who actually make art.

It doesn't entirely succeed as a novel — I never cared what happened to Lacey. But it's a fascinating glimpse of a world few are wealthy, privileged, or determined enough to see. Steve Martin is a collector of fine art, and this novel is not about art so much as its value, whether to an individual or according to the market.

Art as an aesthetic principle was supported by thousands of years of discernment and psychic rewards, but art as a commodity was held up by air.Read an excerpt.

Note, also, that gorgeous artwork is reproduced within.

Art as an intensely personal expression

The Woman Upstairs, by Claire Messud.

There's a lot of hate in this novel's narrator. Nora, gradeschool art teacher, rediscovers her artistic drive when she befriends the immigrant family of a new student, in particular his mother, an artist looking to share a studio.

Messud explores Nora's art-making and its concept, which in turn relies on Nora's interpretation of the art and biographies of Emily Dickinson, Alice Neel, and Edie Sedgwick.

It's said of Edie Sedgwick, but it may as well be about Nora, perhaps Messud herself:

When, as a woman, you make yourself the work of art, and when you are then what everyone looks at, then whatever else, you aren't alone.I can't think of another recent novel that's been so divisive in its reception, so many voices whom I respect decrying that this novel is not worth the hype or critical praise, and it seems to me the lines are clearly drawn along gender and age. For me, that reinforces the point, that art, the creative process, is deeply individual.

Hate it for yourself.

Art for art's sake

What I Loved, by Siri Hustvedt.

I loved this novel. It brought me to tears, wonder, astonishment, despair. It's one of the finest novels I've read, ever.

Written from the point of view of an art historian with some artists as characters, it describes the (near?) contemporary art scene and facets like installation art such that I almost think I understand them.

In equal parts family saga, thriller, meditation, I'd say its primarily about love and loss. But its imbued with art, peopled with artists, who do art, who live and breathe art. It makes not just the characters' artistic visions come alive, but the very idea that there exists such a thing as artistic vision becomes crystal clear, and it makes me wonder how anyone could live without art.

"That's the problem with seeing things. Nothing is clear. Feelings, ideas shape what's in front of you. Cezanne wanted the naked world, but the world is never naked. In my work, I want to create doubt." He stopped and smiled at me. "Because that's what we're sure of."Sample it here.

Coincidentally, I finally downloaded some of Hustvedt's back catalogue last week. And I was thrilled to discover that she has another novel freshly released, The Blazing World, about a woman painter negotiating New York's art establishment.

Plus

Mark Rothko on the Transcendent Power of Art and How (Not) To Experience His Paintings

Labels:

art,

Claire Messud,

Siri Hustvedt,

Steve Martin

Saturday, March 15, 2014

Les Objets crépusculaires

The work of André Dubois is being featured as part of Art Souterrain 2014, showcasing art in the public spaces of Montreal's underground city.

André Dubois cuts fantastically detailed silhouette-like panoramas into things like coffee cups, shoeboxes, maps, and packaging and shines a light on them to cast a shadow image. The series Les Objets crépusculaires blew me away.

The cut-outs constitute a thing of beauty in themselves and are obviously the product of remarkable craftsmanship. Dubois's artistry lies not so much in the final image he creates but in the perspective he has mastered, his ability to understand how an angle of light will translate a flat surface of cuts and gashes into an evocative scene.

Art Souterrain is on for only two weeks (ending tomorrow), but having been on vacation the first week, and playing post-vacation catch-up the second week, I managed to see just a mere fraction of the art on show, at those venues closest to my office.

Happily, Les Objets crépusculaires is on display in the passage between Place Ville-Marie and La Gare Centrale until October 2014, so there's still time for me (for you) to drag friends and family out to see it.

And now I must go slash all my lampshades.

André Dubois cuts fantastically detailed silhouette-like panoramas into things like coffee cups, shoeboxes, maps, and packaging and shines a light on them to cast a shadow image. The series Les Objets crépusculaires blew me away.

The cut-outs constitute a thing of beauty in themselves and are obviously the product of remarkable craftsmanship. Dubois's artistry lies not so much in the final image he creates but in the perspective he has mastered, his ability to understand how an angle of light will translate a flat surface of cuts and gashes into an evocative scene.

Art Souterrain is on for only two weeks (ending tomorrow), but having been on vacation the first week, and playing post-vacation catch-up the second week, I managed to see just a mere fraction of the art on show, at those venues closest to my office.

Happily, Les Objets crépusculaires is on display in the passage between Place Ville-Marie and La Gare Centrale until October 2014, so there's still time for me (for you) to drag friends and family out to see it.

And now I must go slash all my lampshades.

Friday, March 14, 2014

Reasons to read Stefan Zweig

I've only ever read Stefan Zweig's Chess Story, but there is so much more.

Wes Anderson

"It’s more like me trying to do a Zweig-esque thing" (via A Different Stripe).

That Zweig-esque film is The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Zweig biographer George Prochnik interviews Wes Anderson: How a Viennese author inspired The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Beware of Pity

The Sheila Variations: Beware of Pity, by Stefan Zweig

The Outlet: Beware of Memory: On Reading Stefan Zweig's "Beware of Pity"

Letter from an Unknown Woman

The Mookse and the Gripes: Stefan Zweig: Letter from an Unknown Woman

Les derniers jours de Stefan Zweig

Le Figaro: Stefan Zweig au cœur de la tempête

Wes Anderson

"It’s more like me trying to do a Zweig-esque thing" (via A Different Stripe).

That Zweig-esque film is The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Zweig biographer George Prochnik interviews Wes Anderson: How a Viennese author inspired The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Beware of Pity

The Sheila Variations: Beware of Pity, by Stefan Zweig

Although it is, essentially, a domestic tale, a kind of effed-up twisted drawing-room romance of horror (Jane Austen on crystal meth), surrounding it is the world at large, the military maneuvers and gleaming by-rote ritual that seems to give an order and continuity to a crazy world. Zweig knows what is coming, and so do we, which is what gives the book such a creepy pallor.

The Outlet: Beware of Memory: On Reading Stefan Zweig's "Beware of Pity"

Beware is a novel about the complexity of human emotions: about how people hurt one another without meaning to, about how love is as much borne of the happiness one can give as the happiness one can get, and how its absence is inextricably tied up with embarrassment, with shame, with the fear of proclaiming one's love before one's fellow soldiers, fellow men. It is about how Hofmiller grows up, with brutal abruptness, and realizes that he lives in a world far more complex, with boundaries between emotions far more easily blurred, than he expected.

Letter from an Unknown Woman

The Mookse and the Gripes: Stefan Zweig: Letter from an Unknown Woman

This is signature Zweig: highly emotional, almost ridiculously dramatic, yet it works. It works marvelously.

Les derniers jours de Stefan Zweig

Le Figaro: Stefan Zweig au cœur de la tempête

Plongée profonde au cœur de la tempête intérieure qui secoua l'un des grands écrivains du XXe siècle...

Labels:

movie,

Stefan Zweig

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

Homeostatic universe

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. I've heard this phrase thousands of times, often with a hint of humour, referring to various things. I didn't know that it was Winston Churchill who said it, and I didn't know that the statement was in reference to Russia.

In a radio broadcast in October 1939, Churchill said:

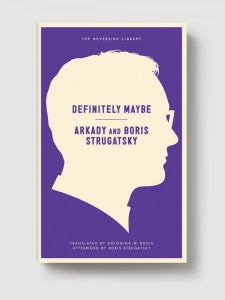

I hesitate to call it science fiction, although that's the label commonly applied to the work of the Strugatsky brothers. It's deeply psychological, with several ambiguities and loose ends. It could also be read as a political satire or social commentary.

Dmitri Alekseevich Malianov, astrophysicist, is on the brink of a great discovery.

And Philip Pavlovich Vecherovsky, state prize laureate.

When they are forced to consider that the orientalist is among their ranks, they realize that it is not merely scientific advances and technological innovation that are being stifled but rather the whole of knowledge of humankind.

Continued reference to Vecherovsky's Martian guffaws lends to the impression that there is something alien among them, even while Vecherovsky is firmest his conviction that he knows what's going on and how best to combat it.

The story is presented in the form of excerpts, all starting with ellipses, sometimes midsentence, but they are presented in order, with no obvious gaps between them. Excerpts of what?

There are so many unresolved situations in this book. It's impossible to state with any certainty which occurrences are purely coincidental or imagined or planned as a joke or part of a grand conspiracy, whether governmental or cosmic in nature.

Roadside Picnic by the Strugatsky brothers, which I read a couple years ago, conveys suspense and horror so palpably; I count it as one of my favourite books ever. Definitely Maybe takes place in a more familiar environment, yet is more mysterious — the enigma it is wrapped in is subtler. It is less about an obvious external threat than a creeping paranoia that's generated from within.

I finished reading Definitely Maybe a couple weeks ago, but I find myself thinking of it often. It is in fact more potent now than when I turned the final page. I continue to consider, with a shudder:

Work toward what end? What price my family, my peace of mind? At what cost knowledge?

See also Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings.

In a radio broadcast in October 1939, Churchill said:

I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.Definitely Maybe, by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

I hesitate to call it science fiction, although that's the label commonly applied to the work of the Strugatsky brothers. It's deeply psychological, with several ambiguities and loose ends. It could also be read as a political satire or social commentary.

I was realizing that just yesterday I was man, a member of society. I had my own concerns and worries, yes, but as long as I obeyed the laws created by the system — and that had become a habit — as long as I obeyed those laws, I was protected from all imaginable dangers by the police, the army, the unions, public opinion, and my friends and family. Now, something in the world around me had gone haywire. Suddenly I became a catfish holed up in a crack, surrounded by monstrous vague shadows that didn't even need huge looming jaws — a slight movement of their fins would grind me into a powder, squash me, turn me into zilch. And it was made clear to me that as long a I hid in that crack I would not be touched. Yet it was even more terrifying than that. I was separated from humanity the way a lamb is cut off from the herd and dragged off somewhere for some unknown reason, while the herd, unsuspecting, goes on about its business, moving farther away into the distance. I would have felt much better if only they had been warlike aliens, some bloodthirsty, destructive aggressors from outer space, from the ocean depths, from the fourth dimension. I would have been one among many; there would have been a place for me, work for me; I would be in the ranks! But I was doomed to perish in front of everyone's eyes. No one would see a thing, and when I was destroyed, ground to dust, everyone would be surprised and then shrug it off.Does that sound more like the threat of an alien intelligence or of government?

Dmitri Alekseevich Malianov, astrophysicist, is on the brink of a great discovery.

In the yellow, slightly curved space, the axially symmetric cavities turned slowly like gigantic bubbles. Matter flowed around them, trying to seep through, but it couldn't. The compressed itself on the boundaries to such incredible densities that the bubbles began to glow.His wife and son have gone to Odessa, leaving him alone with the cat to work. But one interruption (a beautiful woman) follows another (a delivery of vodka and caviar), and soon a full cast is parading through the apartment: Arnold Pavlovich Snegovoi, highly mysterious neighbour, colonel, supposed by Malianov to be a physicist, in rocketry. Valentin Andreevich Weingarten, biologist and womanizer. Zakhar Gubar, master craftsman techie, patent holder of several inventions, lady-killer of the highest degree. Vladlen Semenovich Glukhov, orientalist.

And Philip Pavlovich Vecherovsky, state prize laureate.

Vecherovsky lapsed into muffled guffaws that passed for satisfied laughter. That's probably the sound H.G. Wells's Martians made when they drank human blood; Vecherovsky guffawed like that because he liked the poem he had just read. One would think that the pleasure he derived from poetry was purely physical.All these men are connected, their life's work has been waylaid, the universe is conspiring against them. I find it curious, and commendable, that while the supposed cosmic intelligence is unknowable, there is no hypothesizing about anything like God; for these are men of science (or at least, academic rigour), living under a godless Soviet regime.

When they are forced to consider that the orientalist is among their ranks, they realize that it is not merely scientific advances and technological innovation that are being stifled but rather the whole of knowledge of humankind.

Continued reference to Vecherovsky's Martian guffaws lends to the impression that there is something alien among them, even while Vecherovsky is firmest his conviction that he knows what's going on and how best to combat it.

The story is presented in the form of excerpts, all starting with ellipses, sometimes midsentence, but they are presented in order, with no obvious gaps between them. Excerpts of what?

There are so many unresolved situations in this book. It's impossible to state with any certainty which occurrences are purely coincidental or imagined or planned as a joke or part of a grand conspiracy, whether governmental or cosmic in nature.

Roadside Picnic by the Strugatsky brothers, which I read a couple years ago, conveys suspense and horror so palpably; I count it as one of my favourite books ever. Definitely Maybe takes place in a more familiar environment, yet is more mysterious — the enigma it is wrapped in is subtler. It is less about an obvious external threat than a creeping paranoia that's generated from within.

I finished reading Definitely Maybe a couple weeks ago, but I find myself thinking of it often. It is in fact more potent now than when I turned the final page. I continue to consider, with a shudder:

Work toward what end? What price my family, my peace of mind? At what cost knowledge?

See also Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings.

Labels:

Melville House,

science fiction,

Strugatsky

Tuesday, March 04, 2014

Body mind change

A while ago I attended an exhibit exploring the work of David Cronenberg. That visit included a tour of BMC Labs, after which I engaged in the experience of personalizing my own pod (a biotech enhancement) for brainstem implantation.

At its core a series of psychological profiling questions, the customization process was dressed up with audiovisual clips and social media interactions for an unsettling, emotional, but also weirdly satisfying narrative exercise.

Once calibrated according to my personality, the pod was brought to maturity in optimal lab conditions.

The implantation ceremony was held a few weeks ago. I was unable to attend, but it's been reported on at Fangoria.

My own pod is being delivered to me by mail.

At its core a series of psychological profiling questions, the customization process was dressed up with audiovisual clips and social media interactions for an unsettling, emotional, but also weirdly satisfying narrative exercise.

Once calibrated according to my personality, the pod was brought to maturity in optimal lab conditions.

The implantation ceremony was held a few weeks ago. I was unable to attend, but it's been reported on at Fangoria.

My own pod is being delivered to me by mail.

Labels:

art,

David Cronenberg,

mind

Saturday, March 01, 2014

Mind reading: cognitive poetics

How to read... a mind is a two-week online course starting March 17, offered by the University of Nottingham.

Although I haven't figured out how to read the title of this course, it sounds fascinating, and far too short. I'm going to be an expert in cognitive poetics!

I am positively addicted to MOOCs. (And I love saying "MOOC.") I just finished my fourth MOOC last week, and I start another next week. Only one of them has been purely for personal interest — the rest were for, as they say, professional development. "How to read" (MOOC number six) is a return to feeding my non-working life.

The journey from new student to advanced study is really very short. Over two weeks, you will become fairly expert in cognitive poetics. You will understand in quite a profound way what it is to read and model the minds of other people, both real and fictional. You don't need any preparation other than your curiosity and your own experience of reading literary fiction or viewing film and television drama.

Although I haven't figured out how to read the title of this course, it sounds fascinating, and far too short. I'm going to be an expert in cognitive poetics!

I am positively addicted to MOOCs. (And I love saying "MOOC.") I just finished my fourth MOOC last week, and I start another next week. Only one of them has been purely for personal interest — the rest were for, as they say, professional development. "How to read" (MOOC number six) is a return to feeding my non-working life.

Labels:

cognitive science,

linguistics,

mind,

mooc

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)